“After college I went on a road trip as a ‘carnie,’ a carnival worker, to Northern California, Oregon, and Washington,” Saijo says. “After being on the road for eight months, I stopped off at Weed, California, in a campground, and had an emotional breakdown.”

“I had reached a fork in the road where I felt I had to make a decision, either remain a carnie or dedicate my life to becoming a dedicated working artist,” he explains. “Five beautiful horses way in the distance from the ranch next door came over and I was comforted by these horses reassuring me that I was making the right decision, and that the spirit will not let me down. I literally looked at myself in the mirror (in the 40-foot house trailer that was parked next to the horse ranch), when I made the decision to dedicate my life to fine art and proceed with my art career.”

In the years since, Saijo has established an impressive track record that includes numerous solo and group exhibitions and honors. Born and raised in Los Angeles, Saijo drew upon his influences by media culture (i.e., books, television, movies, magazines) and incorporated media into his art. Materials such as pages from old books become elements in visually striking, multilayered artworks that explore how history and human memory are affected—and often distorted—by textbooks and newspapers and other forms of media. Through his art Saijo has also explored ethnic and cultural themes, including his own Japanese ancestry.

Saijo is one of the contemporary artists featured in the Japanese American National Museum’s exhibition, Instructions to All Persons: Reflections on Executive Order 9066. The exhibition juxtaposes art with historical content about President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s 1942 directive that led to the unconstitutional incarceration of more than 120,000 Japanese Americans during World War II. National debates about recent presidential Executive Orders targeting specific ethnic groups, as well as about the veracity and objectivity of America’s news media, have made both the exhibition and Saijo’s art timely.

The mainstream media industry is losing its credibility, Saijo says. He cites both the changing attitudes of younger generations and controversial breaches, both intentional and not, of classified information by players such as WikiLeaks as factors ushering in a new era.

“I have noticed interesting patterns in term of world view between various generations,” Saijo says. “Mainstream media had a grip on the world view for the past 60 years with television and radio. Most people who grew up with television continue to passively watch television. Whereas the younger generation and young adults who ended up spending more time in front of a computer than a television screen receive a wider variety of information and take a more proactive approach to research and seeking out of information.”

“It seems like people of all ages react to my work,” Saijo says. “How they relate to it really depends on the history of the viewer. If the viewer is familiar with having read a particular book used in the piece it would have a different set of meaning. Or the viewer may see the main image and background pages as texture and take a different approach, more like distant reading. For some it sparks a conversation, and the conversation is what’s meaningful. The work can serve a departure point for discussion.”

“If we can learn to unlearn the programming of cultural assumptions, and begin to realize that we’ve been conditioned to believe in what is to be reality, we learn to peel the layers back and see what is happening for what it is,” Saijo says. “There is a lot of manipulation happening in the mainstream media in the past few years, journalism is no longer what it used to be, there is a lot of effort in the media to shape stereotypes and direct public opinion.”

Questioning assumptions and pushing boundaries have been recurring themes in Saijo’s art practice, which he initially developed through studies at Pasadena City College and ArtCenter College of Design. “At Pasadena City College, I had an instructor named Ben Sakoguchi who encouraged me to pursue fine art. I had a lot of emotional energy built up inside me. He inspired me to start collecting things, break things apart, put things together that don’t go together, and create new meaning out of it. I realized that there are no set rules to art, except the rules that we create for ourselves. It was important to see that it was possible that a Japanese American guy can become a working artist, and to make art about where we come from despite all the prejudice and discrimination we experienced.”

Included in Instructions to All Persons is Saijo’s portrait of the late U.S. Senator Daniel K. Inouye, who lost an arm in battle as an American soldier during World War II en route to becoming a legendary statesman. Saijo says Inouye was an early inspiration to him and remains someone he still thinks about in the present day. “I’ve admired him greatly throughout his career, especially for supporting sovereign tribal land for Native Americans and indigenous peoples.”

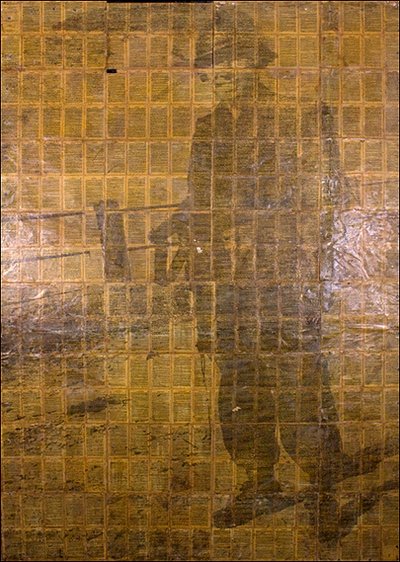

Soldier, Mike Saijo, 1993. Wax, shellac, acrylic, toner on pages of the New Testament Bible on wood panel.

Saijo is thoughtful about parallels and relationships between Japanese Americans and people of other ethnicities. “On a personal level I feel like the history reflected in the exhibition is really about getting together and remembering the past and representing the minority groups that may have been impacted by injustice,” he says. “It’s become necessary (for various groups) to come together as a community…to share and leverage resources, and stand behind and support other minority groups in the face of injustice, because we were there and can understand what it’s like to struggle.”

“In response to the uncertainty of our fragile economy, political unrest, distrust in government leadership, we are reaching the ‘awakening era’ where transparency is opening everything up at its seams and revealing everything within,” Saijo says. But amid the upheaval, he is optimistic about the opportunity for artists and other creative thinkers to influence positive social changes—just as art changed his own life for the better.

“Anything can happen and anything is possible.”

* * * * *

Instructions to All Persons: Reflections on Executive Order 9066

February 18 – August 13, 2017

Japanese American National Museum

Los Angeles, California

© 2017 Darryl Mori